Buffalo Nickel Values

How Much Buffalo Nickels are Worth: Buffalo Nickel Values & Coin Price Chart

Year | Mint | Variety | Designation | VG-8 | F-12 | VF-20 | EF-40 | AU-50 | U-60 | MS-63 | MS-64 | MS-65 | MS-66 | MS-67 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

1800 | P | Plain 4- Stemless Wreath | Red-brown | 200 | 300 | 400 | 500 | 600 | 700 | 800 | 900 | 1000 | 1200 | 1100 |

| Year | Mint | Variety | Designation | VG-8 | F-12 | VF-20 | EF-40 | AU-50 | MS-60 | MS-63 | MS-64 | MS-65 | MS-66 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1913 | (None) Phil | Type 1 | -- | $14 | $15 | $20 | $30 | $28.50 | $80 | $86 | $122 | $250 | $304 |

| 1913 | D | Type 2 | -- | $150 | $170 | $180 | $230 | $275 | $312 | $407 | $530 | $1,300 | $2,110 |

| 1913 | S | Type 2 | -- | $273 | $400 | $480 | $477 | $568 | $859 | $1,210 | $1,560 | $2,908 | $5,250 |

| 1913 | D | Type 1 | -- | $23 | $30 | $35 | $45 | $60 | $120 | $122 | $198 | $405 | $628 |

| 1913 | (None) Phil | Type 2 | -- | $18 | $20 | $25 | $30 | $29.90 | $44 | $94 | $168 | $460 | $859 |

| 1913 | S | Type 1 | -- | $80 | $57 | $130 | $81 | $100 | $151 | $260 | $355 | $795 | $1,472 |

| 1914 | (None) Phil | -- | -- | $20 | $25 | $37 | $50 | $41 | $170 | $135 | $243 | $475 | $1,013 |

| 1914 | (None) Phil | 1914/(3) | -- | $403 | $533 | $598 | $764 | $979 | $2,315 | $5,355 | $9,210 | $21,300 | $67,000 |

| 1914 | D | -- | -- | $99 | $150 | $154 | $240 | $298 | $444 | $529 | $765 | $1,348 | $2,915 |

| 1914 | S | -- | -- | $40 | $50 | $70 | $103 | $146 | $222 | $406 | $769 | $2,194 | $6,295 |

| 1915 | (None) Phil | -- | -- | $7.20 | $10 | $17 | $19.60 | $50 | $170 | $138 | $198 | $508 | $868 |

| 1915 | D | -- | -- | $35 | $60 | $63 | $115 | $153 | $268 | $400 | $618 | $1,390 | $3,650 |

| 1915 | S | -- | -- | $100 | $90 | $250 | $378 | $553 | $821 | $1,488 | $2,060 | $3,090 | $6,000 |

| 1916 | (None) Phil | -- | -- | $6.70 | $7 | $13 | $25 | $24.90 | $100 | $106 | $155 | $300 | $777 |

| 1916 | (None) Phil | Doubled Die Obverse | -- | $7,300 | $9,415 | $12,875 | $20,325 | $27,050 | $66,250 | $145,250 | $247,500 | -- | -- |

| 1916 | D | -- | -- | $25 | $40 | $42 | $100 | $140 | $250 | $307 | $689 | $1,560 | $6,970 |

| 1916 | S | -- | -- | $18 | $30 | $37 | $88 | $180 | $216 | $415 | $919 | $2,905 | $4,690 |

| 1917 | S | -- | -- | $45 | $90 | $130 | $221 | $365 | $1,034 | $1,634 | $2,480 | $3,760 | $6,275 |

| 1917 | (None) Phil | -- | -- | $7.20 | $12 | $17 | $25 | $60 | $200 | $230 | $289 | $504 | $985 |

| 1917 | D | -- | -- | $35 | $100 | $100 | $162 | $315 | $477 | $852 | $1,055 | $2,090 | $5,490 |

| 1918 | (None) Phil | -- | -- | $7.20 | $12 | $15 | $35 | $59 | $177 | $357 | $595 | $1,131 | $2,125 |

| 1918 | D | -- | -- | $25 | $70 | $130 | $230 | $300 | $578 | $1,094 | $1,558 | $3,900 | $7,263 |

| 1918/7 | D | -- | -- | $1,133 | $2,115 | $3,305 | $8,350 | $11,590 | $32,300 | $44,725 | $88,400 | $268,250 | $481,250 |

| 1918 | S | -- | -- | $30 | $59 | $109 | $203 | $378 | $1,043 | $2,860 | $2,819 | $11,590 | $46,500 |

| 1919 | (None) Phil | -- | -- | $4.40 | $8 | $10 | $27 | $34 | $130 | $191 | $315 | $549 | $1,220 |

| 1919 | D | -- | -- | $35 | $50 | $100 | $250 | $390 | $938 | $1,644 | $2,454 | $4,218 | $12,720 |

| 1919 | S | -- | -- | $25 | $54 | $100 | $240 | $450 | $774 | $1,608 | $3,430 | $11,097 | $83,000 |

| 1920 | (None) Phil | -- | -- | $3.20 | $4.60 | $7.20 | $20 | $31 | $160 | $166 | $249 | $671 | $1,199 |

| 1920 | D | -- | -- | $21.50 | $40 | $90 | $320 | $375 | $767 | $1,585 | $2,890 | $4,950 | $55,875 |

| 1920 | S | -- | -- | $10 | $35 | $90 | $160 | $299 | $815 | $1,558 | $3,655 | $11,960 | $49,995 |

| 1921 | (None) Phil | -- | -- | $7.70 | $12 | $27 | $60 | $80 | $251 | $453 | $549 | $950 | $1,530 |

| 1921 | S | -- | -- | $130 | $160 | $270 | $789 | $1,185 | $2,455 | $3,900 | $4,730 | $10,125 | $22,950 |

| 1923 | (None) Phil | -- | -- | $3.70 | $5.70 | $7.80 | $15.50 | $75 | $74 | $207 | $290 | $563 | $1,055 |

| 1923 | S | -- | -- | $10 | $25 | $75 | $175 | $318 | $603 | $1,066 | $1,549 | $4,895 | $42,450 |

| 1924 | S | -- | -- | $50 | $91 | $260 | $780 | $1,535 | $3,085 | $5,023 | $8,225 | $12,500 | $32,167 |

| 1924 | (None) Phil | -- | -- | $6 | $5 | $12 | $25 | $44 | $97 | $274 | $448 | $963 | $2,395 |

| 1924 | D | -- | -- | $13 | $27 | $83 | $160 | $340 | $592 | $1,223 | $1,590 | $4,050 | $11,280 |

| 1925 | (None) Phil | -- | -- | $4.40 | $5 | $8 | $25 | $45 | $54 | $200 | $250 | $433 | $759 |

| 1925 | D | -- | -- | $30 | $43 | $91 | $230 | $348 | $531 | $929 | $1,403 | $3,465 | $10,350 |

| 1925 | S | -- | -- | $13 | $20 | $65 | $195 | $270 | $758 | $1,749 | $2,545 | $12,285 | $91,500 |

| 1926 | (None) Phil | -- | -- | $4 | $4.10 | $8 | $15 | $35 | $43 | $96 | $135 | $245 | $513 |

| 1926 | D | -- | -- | $20 | $33 | $75 | $165 | $312 | $435 | $649 | $1,495 | $4,135 | $8,420 |

| 1926 | S | -- | -- | $50 | $75 | $170 | $599 | $2,158 | $5,060 | $9,570 | $13,700 | $44,495 | $126,500 |

| 1927 | S | -- | -- | $4.80 | $10 | $35 | $109 | $285 | $965 | $2,565 | $3,495 | $14,250 | $38,995 |

| 1927 | (None) Phil | -- | -- | $5 | $3.80 | $5 | $13 | $35 | $140 | $89 | $195 | $321 | $594 |

| 1927 | D | -- | -- | $9.30 | $20 | $37 | $90 | $130 | $245 | $444 | $998 | $3,540 | $21,100 |

| 1928 | (None) Phil | -- | -- | $4 | $3.80 | $5.70 | $12 | $27 | $140 | $160 | $161 | $319 | $457 |

| 1928 | D | -- | -- | $5 | $4.90 | $15.10 | $50 | $51 | $200 | $148 | $210 | $558 | $3,175 |

| 1928 | S | -- | -- | $8 | $7 | $14.70 | $40 | $160 | $330 | $699 | $1,013 | $2,655 | $13,275 |

| 1929 | (None) Phil | -- | -- | $4 | $3.80 | $7 | $12 | $21.30 | $130 | $82 | $130 | $305 | $1,549 |

| 1929 | D | -- | -- | $3 | $7 | $12 | $35 | $60 | $75 | $165 | $273 | $926 | $1,903 |

| 1929 | S | -- | -- | $3 | $2.70 | $4.10 | $17 | $40 | $150 | $143 | $340 | $414 | $904 |

| 1930 | S | -- | -- | $3 | $3.60 | $6 | $17 | $41 | $89 | $164 | $291 | $473 | $946 |

| 1930 | (None) Phil | -- | -- | $3 | $2.80 | $5.20 | $13 | $25 | $120 | $80 | $170 | $270 | $385 |

| 1931 | S | -- | -- | $16.10 | $17.60 | $20.20 | $30 | $55 | $150 | $133 | $180 | $330 | $775 |

| 1934 | (None) Phil | -- | -- | $3 | $2.80 | $4.20 | $13 | $25.50 | $80 | $79 | $160 | $223 | $558 |

| 1934 | D | -- | -- | $3 | $5 | $12 | $22 | $48 | $83 | $153 | $205 | $454 | $1,915 |

| 1935 | (None) Phil | -- | -- | $3 | $4 | $5 | $5 | $8.50 | $50 | $48 | $100 | $130 | $233 |

| 1935 | (None) Phil | Doubled Die Reverse | -- | $68 | $86 | $132 | $465 | $1,029 | $4,590 | $7,850 | $10,450 | $30,250 | -- |

| 1935 | D | -- | -- | $3 | $2.80 | $9 | $17 | $40 | $100 | $101 | $120 | $309 | $828 |

| 1935 | S | -- | -- | $3 | $4 | $5 | $13 | $19.10 | $80 | $73 | $111 | $204 | $421 |

| 1936 | S | -- | -- | $3 | $4 | $3.30 | $7 | $15 | $70 | $48 | $72 | $110 | $242 |

| 1936 | D | -- | -- | $3 | $4 | $3.20 | $7 | $25 | $230 | $52 | $78 | $111 | $220 |

| 1936 | D | 3-1/2 Legs | -- | $675 | $1,107 | $1,605 | $3,680 | $5,463 | $13,000 | $30,000 | -- | -- | -- |

| 1936 | (None) Phil | -- | -- | $3 | $4 | $5 | $7 | $15 | $40 | $49 | $59 | $86 | $175 |

| 1937 | (None) Phil | -- | -- | $3 | $4 | $5 | $5 | $8.50 | $40 | $34 | $42 | $61 | $81 |

| 1937 | D | -- | -- | $3 | $4 | $3.20 | $6 | $8.50 | $55 | $38 | $46 | $77 | $150 |

| 1937 | D | 3 Legs | -- | $494 | $577 | $749 | $893 | $1,779 | $2,710 | $5,584 | $8,820 | $42,995 | $55,495 |

| 1937 | S | -- | -- | $3 | $4 | $5 | $7 | $8.50 | $60 | $37 | $70 | $75 | $120 |

| 1938 | D | -- | -- | $2.30 | $3.10 | $4 | $6 | $8.50 | $1,495 | $32 | $39 | $53 | $77 |

| 1938 | D/S | -- | -- | $10.90 | $12.50 | $14 | $20.20 | $33 | $55 | $81 | $138 | $250 | $235 |

| 1938 | D/D | -- | -- | $4.90 | $6.20 | $7.30 | $9.80 | $14.10 | $100 | $47 | $105 | $109 | $145 |

Description and History

The Buffalo Nickel or Indian Head Nickel as it was sometimes known is perhaps the most iconic of American coins. With a Native American on the obverse and an American Bison on the reverse, the coin truly captures the spirit of the American West. Issued between 1913 and 1938 it was designed by famed sculptor James Earle Fraser.

Following in the great tradition of Augustus Saint-Gaudens and President Teddy Roosevelt, his successor, President William Howard Taft asked Fraser in 1911 to submit a new design for Charles Barber’s Liberty Head Nickel. By 1912, Fraser had submitted several designs with a similar theme – a Native American on the obverse and an American Bison on the reverse. The design was much heralded.

Fraser was awarded $2,500 (Approximately $75,000 today) for his efforts. Minting began, after a slew of minor tweaks and modifications, in 1913. The coins were released into circulation on March 4, 1913, and were lauded by the public but not so by the media. The New York Times printed an editorial that stated “New nickel is a striking example of what a coin intended for wide circulation should not be….. it is not pleasing to look at when new and shiny, and will be an abomination when old and dull.” The NYT editorial completely missed the mark on the public reaction. It is a succinctly American design – Native American Chief on the obverse and an American Bison, which once dominated the Plains, on the reverse.

But as the coins soon entered circulation Treasury officials noted that changes needed to be made. The date and the denomination (FIVE CENTS), soon wore off the coin with increased circulation. The changes that Barber suggested to Fraser and the Treasury officials were to make the numerals in the date on the obverse wider. In addition, the legend “FIVE CENTS” was enlarged. Finally, one additional change was the bison went from standing on a mound to standing on flat ground with a line above the legend “FIVE CENTS” – all of which were intended to keep the date and legends visible for a much longer period of circulation.

Striking these coins was difficult anyway with the metallic composition of .750 Copper and .250 Nickel and having such a complex die to fill. Fraser’s work had intricate designs on the Indian’s hair, braid and feathers. Likewise the Buffalo’s horn, cape and tail were difficult at best to strike up. But as bad as it was for the Philadelphia Mint to accomplish these strikings, the branch mints in Denver and San Francisco had a much more difficult time. Coins dated in the 1920s and struck at these branch mints are notoriously weakly struck.

Fraser’s design, in spite of how the New York Times described it, accomplished EXACTLY what Fraser set out to do. He wanted a coin that was uniquely American and the American Bison was the master of the Plains and the Native American complimented the design. Fraser had the Native American chief – actually a composite of at least 4 Native American chiefs that he sketched- facing right, with the motto “LIBERTY” above and the date below him comprising the obverse elements. The reverse had the American Bison facing left, with the legends “UNITED STATES OF AMERICA” above him and the denomination “FIVE CENTS” below him. The bison model that he used was either the popularly-believed “Black Diamond” who lived at the Central Park Zoo or “Bronx” who did live at the Bronx Zoo.

The 1913 Type I and Type II Nickels each had around 30 million coins struck at the Philadelphia Mint. Both 1913-D coins each had 4 to 5 million struck while each type of S mint had 1 to 2 million minted. 1914 had more than 20 million minted and also produced an overdate 1914/3. 1914 D and S coins through 1919 D and S coins are all better dates.

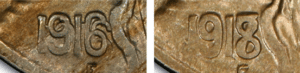

A rarity was created when a 1916/1916 Doubled Date Obverse was minted. Additionally, there is a 1918/7-D that is one of the keys to the Buffalo Nickel series.

Starting with 1920 and continuing to 1926-D, all dates and mintmarks are slightly better with the exceptions being the 1921-S and 1926-S which are scarce dates and worth considerably more than the other early 1920’s dates and mintmarks.

The remaining dates and mintmarks from 1927 through 1938-D are all common dates. The exceptions to that run of dates and mintmarks are the 1935 Double Die Reverse, the 1936-D with 3 ½ legs on the Buffalo, and the 1937-D with the rare and well-known 3-Legged Buffalo, all of these three varieties are RARE!

A pressman at the Denver Mint caused the 1937-D 3-Legged Buffalo error to be struck. He was trying to remove marks on the reverse die that he was using to strike coins and in filing the marks down completely eliminated Buffalo’s right front leg, creating the rarity.